Changing Notions of Masculinity

by Peter Renault

Not so long ago a buddy and I went to see the classic Hitchcock thriller “Rear Window” at a revival movie house. There up on the screen, bigger than life, was the film’s leading man, James Stewart, being massaged by his tough-as-nails maid. At one point Stewart, who is shirtless, flips over, revealing a scrawny chest and the hint of a spare tire around his waist. My friend poked me in the ribs and chuckled that Stewart should have hit the gym more often. But back in 1954 when the movie was released, few would have noticed Stewart’s lack of a six-pack. He was a man’s man, whom women mooned over, and guys looked up to, regardless of his build. Same with other stars of the era: John Wayne, Humphrey Bogart, Robert Mitchum, even James Dean. The exception was Marlon Brando, whose sweat-drenched, sinewy muscles gleaming under a slinky wife-beater left audiences drooling in “A Streetcar Named Desire.”

Notions of what constitutes masculine beauty have constantly evolved over the centuries. The Greeks and Romans idealized the male figure. Body hair was out. Showing skin was in. The word “gymnasium,” let’s not forget, is from the Greek gymnasion meaning “school for naked exercise.” Athletes flaunted their lithe physiques without shame, but the focus was on youth and agility more than muscle mass. In the Middle Ages, bulk triumphed since strength was vital for macho knights decked out in heavy metal. The Renaissance revived ancient standards, but male beauty was still a Platonic ideal, relegated to galleries and museums, not something the average Joe aspired to. Masculinity was a natural asset. You either had it or you didn’t. Muscles were something poor people gained because they had to work hard for a living. The rich preferred having pale skin and soft shapes. In 19th-century England, Beau Brummels catered more to their dapper clothes than to their frames, although the popularity of boxing later on in Victorian circles encouraged the occasional manly physique.

For the population at large, however, exercise was still an exotic pastime, something to ogle, but not to emulate. Eugene Sandow, arguably the world’s first professional fitness model, was treated as a kind of novelty act, appearing on stage and at fairs. Likewise Houdini who was as much a draw for his muscle tone as for his magic tricks. Hollywood had its share of hunks, most notably Johnny Weissmuller, who won gold in swimming at the Olympics, then starred in a dozen or more Tarzan films but could never land serious roles. So too Olympian Buster Crabbe who showed off his gold-winning swimmer’s build to advantage as Flash Gordon. Later, Steve Reeves lorded over sword-and-sandal flicks as Hercules, but never made it big in regular films. It really wasn’t until the late 20th-century that having a buff physique finally came into vogue in the mainstream. Now it’s almost mandatory.

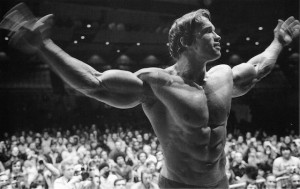

When did our attitudes change? One could argue it happened when Schwarzenegger, Stallone and Van Damme became enormous box-office stars. Gradually the focus in films shifted from meaty character roles to action-packed beefcake. A leading man today must appear toned to get the juicy parts and lure the crowds. Henry Cavill in the latest Superman picture looks amazing in his “Man of Steel” uniform, but it’s almost superfluous. He’s already superhuman looking, a far cry from the rather portly George Reeves of the early TV series. Then there’s Daniel Craig as the “aesthetic” James Bond, rising from the surf like a demigod in a form-fitting speedo. He definitely upped the ante for secret agents and the like. Even Matt Damon, best known for the Bourne series, won praise recently in the Emmy-nominated Liberace biopic on HBO, “Behind the Candelabra,” when he bared his buff torso and glutes for the camera.

The trickle-down effect of all this hyper-masculinity on film and in television is that the male population today is increasingly keen on having a killer bod, and prepared to work overtime and spend major bucks to achieve it. It’s not enough anymore to “just be another pretty face.” Male fitness is now big business. Men are spending upwards of $5 billion a year on grooming products. Billions more are spent on gyms and health clubs and exercise equipment. Factor in dough spent on vitamins, supplements, tanning salons, and spa treatments, as well as cosmetic surgery, and the numbers are simply staggering. Achieving a masculine look these days may be expensive, but it’s become just another part of a man’s standard of living.

It’s no coincidence that when they cast “Disturbia,” a hip retelling of “Rear Window,” they didn’t hire an average-looking guy in his mid-40s for the lead. They chose 20-something Shia LaBoeuf who may not have been everyone’s idea of the stud next door, but who definitely did not have to worry about sporting a spare tire.